The Epic of China’s Agrarian Civilization — A Brief Analysis of The Classic of Poetry · The Seventh Month, Stanza 1-5

- Hongji Wang

- Nov 12, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Nov 15, 2025

The Seventh Month (《七月》) is a renowned masterpiece from The Classic of Poetry (《詩經》). Among the "Three Hundred Poems," few works so systematically and comprehensively depict the realities of China’s early agrarian society. Through this poem, later generations are able to gain an organized understanding of social life in ancient times. For this reason, The Seventh Month is included in nearly all major anthologies of The Classic of Poetry.

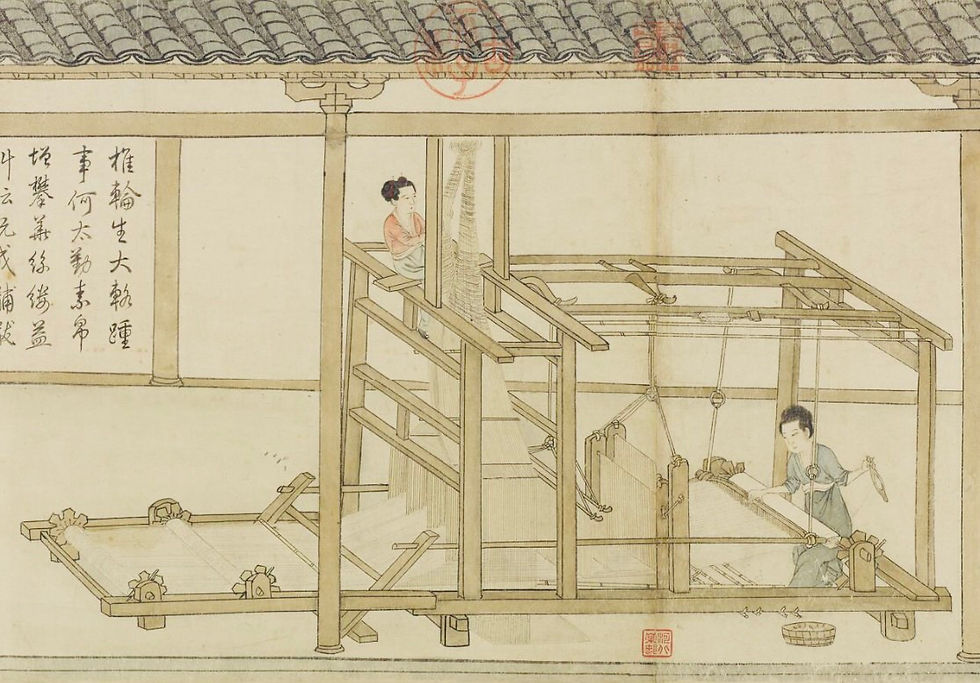

It is also the longest poem in the collection, consisting of eight stanzas and 118 lines, systematically describing a sequence of activities such as spring plowing, autumn harvest, winter storage, silk production, dyeing, sewing, hunting, house repair, winemaking, corvée labor, and banquets.

The Qing scholar Fang Yurun commented in Origins of the Classic of Poetry

"In the Bin section, only The Seventh Month speaks entirely of agriculture and sericulture. Without personal experience tilling the fields, one could not have written with such intimacy and vividness."

Indeed, Fang’s observation is most accurate. The Seventh Month can rightfully be called an epic of agrarian life. It presents before us a vivid tableau of agricultural existence in China over three thousand years ago, enabling us to glimpse the authentic rhythms of early rural society. Its value lies not merely in literature, but even more in its historical significance.

Although widely transmitted, The Seventh Month has often been misinterpreted due to the abundance of archaic and technical terms within it. Many traditional commentaries explain only isolated words or lines, without providing coherent interpretations of entire stanzas. This makes it difficult for readers to grasp the poem’s underlying logic and its faithful reflection of historical reality. While the present writer cannot claim to resolve all complexities, an attempt will be made to present the poem’s true face.

The Seventh Month does not convey intense personal emotions, nor is it, as some later scholars have argued, a veiled critique of the ruling class. Rather, it reflects in a genuine and unembellished manner the lifestyle of our agrarian ancestors. It is a record and depiction of original human existence, and only upon this premise can the poem be properly understood. What follows is a line-by-line interpretation intended to assist readers in comprehending its meaning.

The original poem:

Stanza 1

In the seventh month, the Fire Star descends;

七月流火,

In the ninth month, winter clothes are prepared.

九月授衣。

On days of the first, the wind blows like a horn;

一之日觱發,

On days of the second, it grows piercing cold.

二之日栗烈。

Without robes or coarse garments, how can one endure the year’s end?

無衣無褐,何以卒歲。

On days of the third, the plows are prepared;

三之日於耜,

On days of the fourth, they step into the fields.

四之日舉趾。

With wife and children together, bringing food to the southern fields;

同我婦子,饁彼南畝,

When the overseer of the fields arrives, his heart rejoices.

田畯至喜。

Stanza 2

In the seventh month, the Fire Star descends;

七月流火,

In the ninth month, winter clothes are prepared.

九月授衣。

In the spring days, the sun grows warm;

春日載陽,

The oriole sings.

有鳴倉庚。

Women carry fine baskets;

女執懿筐,

They follow the narrow paths;

遵彼微行,

There they seek tender mulberry leaves.

爰求柔桑。

The spring days linger long;

春日遲遲,

The gatherers of wild herbs are many;

採蘩祁祁,

Yet the women’s hearts are sorrowful,

女心傷悲,

Fearing they may be taken home by the noble sons.

殆及公子同歸。

Stanza 3

In the seventh month, the Fire Star declines;

七月流火,

in the eighth, reeds and rushes flourish.

八月萑葦。

In the silkworm month, they prune the mulberry branches;

蠶月條桑,

With axes and hatchets, they cut the long boughs;

取彼斧斨,以伐遠揚,

Ah, those tender mulberry shoots!

猗彼女桑。

In the seventh month, the shrike cries;

七月鳴鵙,

In the eighth, they weave again.

八月載績。

They weave black and yellow threads;

載玄載黃,

My bright crimson cloth shines resplendent;

我朱孔陽,

To make garments for the noble sons.

為公子裳。

Stanza 4

In the fourth month, the crops begin to head;

四月秀葽,

In the fifth, cicadas sing.

五月鳴蜩。

In the eighth, the harvest is gathered;

八月其獲,

In the tenth, the leaves fall.

十月隕籜。

On days of the first, they hunt the raccoon dogs;

一之日於貉,

They take the foxes;

取彼狐狸,

To make fur robes for the noble sons.

為公子裘。

On days of the second, they continue their martial skill;

二之日其同,載纘武功,

Keeping the young boars, they offer the grown ones to the lord.

言私其豵,獻豜於公。

Stanza 5

In the fifth month, the grasshoppers move their thighs;

五月斯螽動股,

In the sixth, the green crickets flutter their wings;

六月莎雞振羽,

In the seventh, the crickets sing in the fields;

七月在野,

In the eighth, beneath the eaves;

八月在宇,

In the ninth, at the door;

九月在戶,

In the tenth, the crickets creep under the bed.

十月蟋蟀入我床下。

They sweep the house and smoke out the rats;

穹窒熏鼠,

They seal the windows and plaster the doors.

塞向墐戶。

Alas, my wife and children!

嗟我婦子,

The year is changing; let us dwell inside this room.

曰為改歲,入此室處。

Stanza 6

In the sixth month, they have wine and grape jam;

六月食鬱及薁,

In the seventh, they enjoy malva crispa and beans;

七月亨葵及菽,

In the eighth, they beat down jujubes;

八月剝棗,

In the tenth, they harvest rice;

十月獲稻,

For this they brew spring wine, to bless enduring years with long brows.

為此春酒,以介眉壽。

In the seventh month, they eat melons;

七月食瓜,

In the eighth, they cut the gourds;

八月斷壺,

In the ninth, they gather hemp seeds;

九月叔苴,

They pluck sow thistle, and cut ailanthus for firewood,

採荼薪樗,

thus are our farmers fed.

食我農夫。

Stanza 7

In the ninth month, they build threshing yards and gardens;

九月築場圃,

In the tenth, they store the grain.

十月納禾稼。

Millet and glutinous millet, late grain and early grain;

黍稷重穋,

rice, hemp, beans, and wheat—

禾麻菽麥,

Alas, my farmers!

嗟我農夫。

Our harvest is done, now we must go to repair the granaries.

我稼既同,上入執宮功。

By day you thatch with straw, by night you twist ropes.

晝爾於茅,宵爾索綯。

Swiftly you mend the lofty roofs, so to begin souring the hundred grains.

亟其乘屋,其始播百穀。

Stanza 8

On days of the second, they hew the ice – clang, clang;

二之日鑿冰沖沖,

On days of the third, they store it in the icy cellar.

三之日納於凌陰。

On days of the fourth, in early spring,

四之日其蚤,

They offer lamb and chives in sacrifice.

獻羔祭韭。

In the ninth month, frost descends austere;

九月肅霜,

In the tenth, they cleanse the threshing square.

十月滌場。

They line the wine in solemn array;

朋酒斯饗,

They slay the lamb for the sacred day.

曰殺羔羊。

Ascending the lord’s hall, they raise the vessel of wine;

躋彼公堂,稱彼兕觥,

Wishing for boundless longevity.

萬壽無疆。

Stanza One

Here, The Seventh Month follows the Zhou dynasty calendar, not the Xia dynasty calendar traditionally used in agriculture. The first line quotes a farming proverb, hence it uses the Zhou dynasty calendar. The seventh month in the Zhou calendar corresponds to the Shen month, associated with metal (one element of Wu Xing), and marks the approach of autumn. "火 (huǒ)" refers to Antares among the Chinese twenty-eight lunar mansions, also known as the Great Fire Star. In the Zhou dynasty calendar, during the fifth month, it appears due south at dusk; by the sixth month, it has already sunk westward—thus "流 (liú)," meaning decline. The ninth month corresponds to the Xu month, associated with earth (one element of Wu Xing), marking the end of autumn and the impending arrival of winter; therefore, one must prepare winter garments. "授衣 (shoù yī)" means not "to bestow clothes," but "to assign women the work of making winter clothes."

In the phrase "on the days of the first ( 一之日)," the calendar referred to is the Xia dynasty calendar, the agricultural calendar used in early China. In the Xia dynasty calendar system, the month of Zi (the first month) corresponds to the eleventh month in the Zhou dynasty calendar. Therefore, this phrase could be understood as "the days of the eleventh month." By the same logic, "the days of the second ( 二之日) " refers to the twelfth month in the Zhou dynasty calendar.

Since the lunar calendar used today (the so-called "Chinese agricultural calendar") was established in the Han dynasty, largely following the Zhou dynasty calendar, there exists a discrepancy between the Xia and Zhou dynasty calendars. In other words, what is now the eleventh lunar month corresponds to the first month of the Xia calendar. With this understanding, the expressions "days of the first", "days of the second", and "days of the third" in The Seventh Month can be properly interpreted. Many scholars who have studied The Seventh Month have long avoided addressing a central question: why do the months in the poem appear so inconsistent? It begins with "the seventh month," later mentions "the ninth month," then "the first," and even "the fourth." This apparent disorder in the sequence of months has long been a major obstacle to understanding the poem. Traditional commentators tended to explain only individual words, without reconstructing the temporal or logical structure of the text, leaving readers confused.

In fact, there are two main reasons for this seeming inconsistency. First, The Seventh Month is organized not by calendar order, but by the sequence of agricultural and social activities throughout the year — spring plowing, silkworm breeding, cloth making, hunting, house repairing, autumn harvest, winter storage, and ritual offerings. When mentioning one activity, the writer describes nearly all the important tasks of a year together, and so the temporal order naturally appears interwoven and sometimes reversed. This poem is not a chronological record, but a record of activities, so its sequence is governed by thematic logic rather than time.

Second, the confusion also arises from the use of two calendar systems. The first four stanzas seem out of order because their opening lines are actually ancient agricultural proverbs, which express the theme of each stanza rather than mark the time. These proverbs were believed to have originated from the Zhou ancestors, so whenever a proverb contains the character "month (月)," it follows the Zhou dynasty calendar; if it does not mention "month (月)," it follows the Xia dynasty calendar. This explains why the time references appear inconsistent — though in reality, they are not. For this reason, the opening lines of the first and second stanzas are repeated.

The phrase "觱發 (bì bó)" describes the sound of the wind. "觱 (bì)" refers to a horn made from animal horns by the Western Qiang people, used to call horses. Its sound is deep and muffled, resembling the moaning of the wind. Thus, the line evokes the sound of cold wind blowing like the call of the Bi Horn. "栗烈 (lì liè)," also written as "凓冽," meaning "bitingly cold wind." "衣 (yī)" refers to ceremonial clothing, while "褐 (hè)" means coarse cloth working clothes. "舉趾 (jǔ zhǐ)” means “to lift one’s feet,” i.e., to go down to the fields to work. "饁(yè)" means “to deliver meals,” and "南畝 (Nán mǔ)" means “southern fields,” here referring generally to farmland where labor takes place. "田畯( Tián jùn)" was an ancient agricultural officer. "至喜(Zhì xǐ)" means "very pleased."

Thus, the first stanza portrays spring plowing and the hardships of early-year agricultural preparation. Its meaning in modern language can be rendered as:

The old proverb says: “In the seventh month the Fire Star descends; in the ninth month, one prepares winter clothes.” In the eleventh month, the cold wind roars like a horn; by the twelfth, the frost bites deeply. Without sufficient clothing, how could one endure the winter? In the first month of spring, farmers ready their tools. In the second, they begin plowing. Accompanied by wife and children, carrying food to the southern fields, they labor joyfully—so much so that even the overseer smiles to see them.

Stanza 2

The phrase "載陽 (zài yáng)" refers to the warming sunlight of spring. "春日 (chūn rì)" here denotes the third month in the Zhou dynasty calendar. "倉庚 (cāng gēng)" is the oriole, a yellow bird regarded as an agricultural timekeeper — when it begins to sing, it signals that the season for gathering mulberry leaves and wild greens has arrived.

"懿筐 (yì kuāng)" means a deep basket used for collecting vegetables or mulberry leaves. "微行 (wēi háng)" refers to small country paths. "柔桑 (róu sāng)" means tender mulberry leaves. "蘩 (fán)" is white mugwort, which can be used to pad silkworm baskets. "祁祁 (qí qí)" originally described high, continuous hills, but here it metaphorically refers to the large number of women engaged in mulberry gathering. "殆 (dài)" means “to be afraid” or “to worry.”

The second stanza depicts the activity of mulberry gathering and springtime labor. Its meaning in modern language can be rendered as:

An ancient farming proverb says: when the Great Fire Star sets in the seventh month, by the ninth month one must prepare winter clothing. In the warm spring days of the third month, the sun hangs high in the sky, and the oriole’s song echoes through the fields, urging the mulberry-picking girls to lift their deep baskets and follow the narrow country paths to pluck tender mulberry leaves. The spring sun lingers long before setting, and the girls gathering white mugwort move one after another in endless lines. As they pick mulberry leaves and mugwort, they chat and laugh — yet some quietly worry: will they be seized and forced into marriage by the noble young lords they dislike?

Stanza 3:

"萑 (huán)" refers to a kind of grass similar to reeds, and "葦 (wěi)", meaning common reeds. The writer mentions them because they can be used to weave shallow baskets for raising silkworms; thus, these two lines of ancient farming proverbs are cited. "蠶月 (Cán yuè)" refers to the third month in the Zhou dynasty calendar — the silkworm-raising season. "條 (tiáo)" here is a noun used as a verb, meaning to prune branches. "條桑 (tiáo sāng)" means to trim the branches of mulberry trees.

"斧 (fǔ)" refers generally to heavy cutting tools, while "斨 (qiāng)" is a type of axe used for splitting wood. "遠揚 (yuǎn yáng)" means "long branches." "女桑 (nǚ sāng)" refers to tender mulberry leaves. "鵙 (jú)" is the shrike, a fierce insect-eating and mouse-catching bird; when it sings, it signals that autumn is near. "績 (jì)" means "to spin" or "to weave." "載 (zài)" means “again.” Thus, "載玄載黃 (zài xuán zài huáng)" means "both black and yellow." "孔陽 (kǒng yáng)" means "very bright."

The third stanza describes sericulture (silkworm raising) and weaving. Its meaning in modern language can be rendered as:

An ancient proverb says: when the Great Fire Star sets in the seventh month, in the eighth month, one must harvest Huan and Wei reeds in time. In the warm spring of the third month, people prune the mulberry trees, using axes to cut away overly long branches so the trees will grow stronger. They pull down the branches and pluck the tender mulberry leaves. When the shrike sings, the women are busy weaving cloth. The fabric they weave is dyed black and yellow; the brocade, bright red and brilliant, is made to clothe noble young lords.

Stanza 4:

The phrase "秀葽 (xiù yāo)" describes crops just about to form ears, not yet mature. The character "要 (yāo)" originally depicts two hands placed on the waist; with the grass radical added, it refers to a plant whose "waist" has thickened—about to head. The scholar Zheng Xuan thought it referred to the Wang melon, but that is only a conjecture without evidence. "蜩 (tiáo)" means “cicada,” which begins to sing around the fifth month in the Zhou dynasty calendar.

"隕箨 (yǔn tuò)" describes the withering and falling of leaves; in character form, it literally means “the tree chooses what to shed.” These first four lines are ancient farming proverbs quoted to emphasize agricultural rhythms. "貉 (hé)" refers to the raccoon dog, an animal resembling a fox whose fur was highly valued for winter clothing—it was one of the main targets of winter hunting. "纘 (zuǎn)" means "to continue" or "to carry on." "武功 (wǔ gōng)" refers to hunting skills or martial training. "豵 (zòng)" means a one-year-old piglet, and "豜 (jiān)" means a full-grown boar.

The fourth stanza focuses on the hunting life. Its modern meaning can be rendered as:

In the fourth month of the Zhou dynasty calendar, the crops begin to head. By the fifth month, the cicadas sing even louder. In the eighth month, the harvest begins, and by the tenth month, the leaves of the trees start to fall. In the eleventh month, people hunt raccoon dogs and foxes, choosing the finest pelts to make fur coats for noble lords. (Note: because these agricultural proverbs follow the Zhou dynasty calendar, the tenth month here corresponds to the eleventh month in the summer calendar, showing seasonal continuity.) In the twelfth month, hunting and martial training continue. The young wild boars of one year are kept for breeding, while the large boars of three years are offered as tribute at the public hall.

Stanza 5:

The phrase "斯螽 (sī zhōng)" refers to the "螽斯 (zhōng sī)," also known as the grasshopper or locust. "動股 (dòng gǔ)" describes the rubbing of its hind legs that produces its chirping sound. In the fifth month, as the weather enters the hottest period of the year, the hotter it gets, the louder the grasshoppers sing — marking the crucial time when crops are filling their grains. "莎雞 (suō jī)" is the katydid, a green, spindle-shaped insect that makes a “Shasha” sound, also a sign of midsummer heat.

"七月在野 (qī yuè zài yě)" means that in the seventh month, the crickets chirp outdoors in the wild. By the eighth month, as autumn approaches, they leap up to sing beneath the eaves. By the ninth month, they crawl into the house, and by the tenth month, they hide beneath the bed. "穹 (qióng)" means "house interior," and "窒 (zhì)" means “to clean out.” Thus, "穹窒 (qióng zhì)" means to thoroughly clean the house. "熏鼠 (xūn shǔ)" means “to smoke out the mice,” driving them away with smoke. "塞 (sè)" means “to seal,” and "向 (xiàng)" here refers to the north window — "塞向 (sè xiàng)" thus means “to block the north window” to prevent cold winds from entering. "墐戶 (jìn hù)" means “to plaster or seal the door cracks with mud,” also to keep out wind and insects. "改歲 (gǎi suì)" means "to pass into the new year," and "處 (chǔ)" means “to dwell” or “to live.”

The fifth stanza primarily quotes a series of old farming proverbs. On the surface, it speaks about insects, but in essence, it describes the natural rhythm marking the transition from summer to winter. By observing and listening to the insects, farmers could tell the approach of seasonal change. Once they recognized the steps of the seasons, they knew it was time to make preparations — to clean and repair the house in advance, sealing it up tightly for the coming cold. When the new year arrives, a new guardian spirit of the year takes charge — a most significant moment in the agricultural calendar, demanding careful attention and reverence.

(To be continued)

_edited.png)

Comments